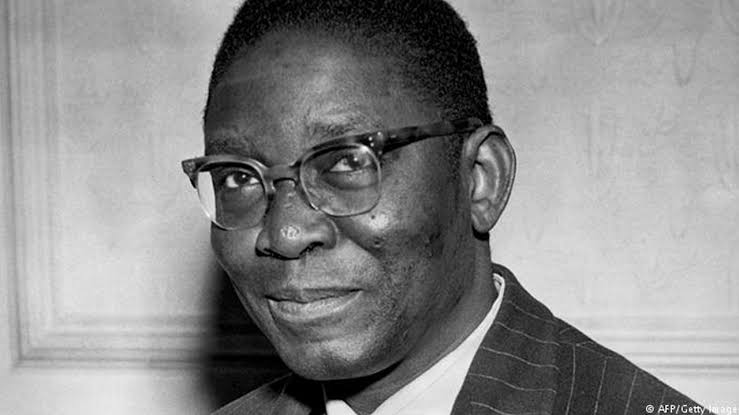

NNAMDI AZIKIWE

A legend is someone who spent his life and time performing a greater cause, while a hero, according to Christopher Reeve, is an individual who finds the strength to persevere in spite of overwhelming obstacles. Suffice it to say that Right Honouraable Dr. Nnamdi Benjamin Azikiwe, Owelle of Onitsha is both a hero and a legend.

EARLY LIFE

Born on November 16, 1904 and died on May 11, 1996, Dr. Azikiwe, popularly known as “Zik of Africa”, was a Nigerian statesman and political leader, who served as the first President of Nigeria from 1963 to 1966. Considered a driving force behind the Nigeria’s independence, Zik came to be known as the “father of Nigerian Nationalism”.

Zik’s father, Obed-Edom Chukwuemeka Azikiwe, born in 1879 and died on March 3, 1958 (two months after the death of his loving wife), Onye Onicha Ado na Iduu, was a clerk in the British Administration of Nigeria. He traveled extensively as part of his job. Nnamdi Azikiwe’s mother was Rachel Chinwe Ogbenyeanu Azikiwe, born in 1883 and died in January 1958. She was popularly called Nwanonaku and was the third daughter of Aghadiuno Ajie. Her family descended from a royal family in Onitsha, and her paternal great-grandfather was Obi (Ugogwu) Anazenwu. Nnamdi Azikiwe had one sister named Cecilia Eziamaka Arinze.

EDUCATION

As a young boy, Nnamdi spoke Hausa very well. His father, concerned about his son’s fluency in Hausa and not Igbo, sent him to Onitsha in 1912 to live with his paternal grandmother and aunt. In Onitsha, Nnamdi Azikiwe attended Holy Trinity School (a Roman Catholic mission school) and Christ Church School (an Anglican primary school).

In 1914, while his father was working in Lagos, Nnamdi was bitten by a dog; this prompted his worried father to ask him to come to Lagos to heal and to attend school in the city. His father was transferred to Kaduna two years later, and Zik briefly lived with a relative who was married to a Muslim from Sierra Leone.

In 1918, he was back in Onitsha and finished his elementary education at CMS Central School. Zik then worked at the school as a student-teacher, supporting his mother with his earnings. In 1920, his father was posted back to southern Nigeria in Calabar. Nnamdi joined his father in Calabar, beginning secondary school at the Hope Waddell Training College. He was introduced to the teachings of Marcus Garvey, Garveyism, which became an important part of his nationalistic rhetoric.

After attending Hope Waddell, Nnamdi Azikiwe was transferred to Methodist Boys’ High School, Lagos. There, he befriended classmates from old Lagos families such as George Shyngle, Francis Cole and Ade Williams (a son of the Akarigbo of Remo). These connections were later beneficial to his political career in Lagos.

Zik heard a lecture by James Aggrey, an educator who believed that Africans should receive a college education abroad and return to effect change. After the lecture, Aggrey gave the young Azikiwe a list of schools accepting black students in America. After completing his secondary education, Azikiwe applied to the colonial service and was accepted as a clerk in the Treasury Department. His time in the colonial service exposed him to racial bias in the colonial government.

OVERSEA TRIP

Determined to travel abroad for further education, Nnamdi Azikiwe applied to universities in the U.S. He was admitted by Storer College, contingent on his finding a way to America. To reach America, he contacted a seaman and made a deal with him to become a stowaway. However, one of his friends on the ship became ill and they were advised to disembark in Sekondi. In Ghana, Azikiwe worked as a police officer; his mother visited, and asked him to return to Nigeria. He returned, and his father was willing to sponsor his trip to America.

Zik attended Storer College’s two-year preparatory school in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. To fund his living expenses and tuition, he worked a number of menial jobs before enrolling in Howard University in Washington, D.C. in 1927 to obtain a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science.

In 1929, he transferred from Howard University to Lincoln University to complete his undergraduate studies and graduated in 1930 with a BA in Political Science. Thereafter, Zik enrolled at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and in the University of Pennsylvania simultaneously in 1930, receiving a master’s degree in Religion from Lincoln University and a master’s degree in Anthropology from the University of Pennsylvania in 1932. He later became a graduate-student instructor in the history and political-science departments at Lincoln University, where he created a course in African history. He was a candidate for a doctoral degree at Columbia University before returning to Nigeria in 1934.

Azikiwe’s doctoral research focused on Liberia in world politics, and his research paper was published by A. H. Stockwell in 1934. During his time in America, he was a columnist for the Baltimore Afro-American, Philadelphia Tribune and the Associated Negro Press.

Zik applied as a foreign-service official for Liberia, but was rejected because he was not a native of the country. By 1934, when Azikiwe returned to Lagos, he was well-known and viewed as a public figure by some members of the Lagos and Igbo community. He was welcomed home by a number of people, as his writings in America evidently reached Nigeria.

JOURNALISM CAREER

In Nigeria, Zik’s initial goal was to obtain a position commensurate with his education; after several unsuccessful applications (including for a teaching post at King’s College), he accepted an offer from Ghanaian businessman, Alfred Ocansey, to become founding editor of the African Morning Post (a new daily newspaper in Accra, Ghana).

Zik was given a free hand to run the newspaper. So, he recruited many of its original staff. Azikiwe wrote “The Inside Stuff by Zik”, a column in which he preached radical nationalism and black pride, which raised some alarm in colonial circles. As editor, he promoted a pro-African nationalist agenda. In his passionately denunciatory articles and public statements, he censured the existing colonial order: the restrictions on the African’s right to express their opinions, and racial discrimination. Zik also criticized those Africans who belonged to the ‘elite’ of colonial society and favoured retaining the existing order, as they regarded it as the basis of their well-being.

During Azikiwe’s stay in Accra, he advanced his New Africa philosophy later explored in his book, Renascent Africa. Zik did not shy away from Gold Coast politics. The Post published a May 15, 1936 article, “Has the African a God?” by I. T. A. Wallace-Johnson, and Azikiwe (as editor) was tried for sedition. He was originally found guilty and sentenced to six months in prison, but his conviction was overturned on appeal.

Nnamdi Azikiwe returned to Lagos in 1937 and founded the West African Pilot, a newspaper, which he used to promote nationalism in Nigeria. In addition to the Pilot, his Zik Group established newspapers in politically and economically-important cities throughout the country. The group’s flagship newspaper was the West African Pilot, which used Dante Alighieri’s “Show the light and the people will find the way” as its motto.

Other publications were the Southern Nigeria Defender from Warri (later Ibadan), the Eastern Guardian (founded in 1940 and published in Port Harcourt), and the Nigerian Spokesman in Onitsha.

In 1944, the group acquired Duse Mohamed’s Comet. Azikiwe’s newspaper venture was a business and political tool. He founded other business ventures (such as the African Continental Bank and the Penny Restaurant) at this time, and used his newspapers to advertise them.

Before World War II, the West African Pilot’s editorials and political coverage focused on injustice to Africans, criticism of the colonial administration and support for the ideas of the educated elites in Lagos. However, by 1940 a gradual change occurred. As he did in the African Morning Post, Zik of Africa began writing a column “Inside Stuff” in which he sometimes tried to raise political consciousness.

Pilot editorials called for African independence, particularly after the rise of the Indian independence movement. Although the paper supported Great Britain during the war, it criticized austerity measures such as price controls and wage ceilings.

In 1943, the British Council sponsored eight West African editors (including Azikiwe). He and six other editors used the opportunity to raise awareness of possible political independence. The journalists signed a memorandum calling for gradual socio-political reforms, including abrogation of the crown colony system, regional representation and independence for British West African colonies by 1958 or 1960. The memorandum was ignored by the colonial office, increasing Zik’s militancy.

Zik had a controlling interest in over 12 daily, African-run newspapers. He revolutionized the West African newspaper industry, demonstrating that English-language journalism could be successful. By 1950, the five leading African-run newspapers in the Eastern Region (including the Nigerian Daily Times) were outsold by the Pilot.

On July 8, 1945, the Nigerian government banned Zik’s West African Pilot and Daily Comet for misrepresenting information about a general strike. Although Zik acknowledged this, he continued publishing articles about the strike in the Guardian (his Port Harcourt newsletter). In August, the newspaper was allowed to resume publication.

Zik raised the alarm about an assassination plot by unknown individuals working on behalf of the colonial government. His basis for the allegation was a wireless message intercepted by a Pilot reporter. After receiving the intercepted message, Azikiwe went into hiding in Onitsha. The Pilot published sympathetic editorials during his absence, and many Nigerians believed the assassination story.

Azikiwe’s popularity, and his newspaper circulation, increased during this period.

POLITICAL CAREER

Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe became active in the Nigerian Youth Movement (NYM), the country’s first nationalist organization. Although he supported Samuel Akisanya as the NYM candidate for a vacant seat in the Legislative Council in 1941, the NYM executive council selected Ernest Ikoli. Azikiwe resigned from the NYM, accusing the majority Yoruba leadership of discriminating against the Ijebu-Yoruba members and Igbos. Some Ijebu members followed him, splitting the movement along ethnic lines.

Zik entered politics, co-founding the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) with Herbert Macaulay in 1944. Azikiwe became the council’s Secretary-General in 1946.

A militant youth movement, led by Osita Agwuna, Raji Abdalla, Kolawole Balogun, M. C. K. Ajuluchukwu and Abiodun Aloba, was established in 1946 to defend Zik’s life and his ideals of self-government. Inspired by his writings and Nwafor Orizu’s Zikism philosophy, members of the movement soon began advocating positive, militant action to bring about self-government.

Calls for action included strikes, study of military science by Nigerian students overseas, and a boycott of foreign products. Zik did not publicly defend the movement, which was banned in 1951 after a failed attempt to kill a colonial secretary.

In 1945, British governor, Arthur Richards, presented proposals for a revision of the Clifford constitution of 1922. Included in the proposal was an increase in the number of nominated African members to the Legislative Council. However, the changes were opposed by nationalists such as Zik. NCNC politicians opposed unilateral decisions made by Arthur Richards and a constitutional provision allowing only four elected African members; the rest would be nominated candidates. The nominated African candidates were loyal to the colonial government, and would not aggressively seek self-government.

A tour of the country was begun to raise awareness of the party’s concerns and to raise money for the UK protest. NCNC president, Herbert Macaulay, died during the tour, and Azikiwe assumed leadership of the party. He led the delegation to London and, in preparation for the trip, traveled to the US to seek sympathy for the party’s case.

Zik met Eleanor Roosevelt at Hyde Park, and spoke about the “emancipation of Nigeria from political thralldom, economic insecurity and social disabilities”. The UK delegation included Azikiwe, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, Zanna Dipcharima, Abubakar Olorunimbe, Adeleke Adedoyin and Nyong Essien.

The delegation submitted its proposals to the colonial secretary, but little was done to change to Richards’ proposals. The Richards constitution took effect in 1947, and Zik contested one of the Lagos seats to delay its implementation.

Under the Richards constitution, Zik was elected to the Legislative Council in a Lagos municipal election from the National Democratic Party (an NCNC subsidiary). He and the party representative did not attend the first session of the council.

Agitation for changes to the Richards constitution led to the Macpherson constitution. The Macpherson constitution took effect in 1951 and, like the Richards constitution, called for elections to the regional House of Assembly. Zik opposed the changes, and contested for the chance to change the new constitution. Staggered elections were held from August to December 1951. In the Western Region (where Azikiwe stood), two parties were dominant: Azikiwe’s NCNC and the Action Group. Elections for the Western Regional Assembly were held in September and December 1951 because the constitution allowed an electoral college to choose members of the national legislature; an Action Group majority in the house might prevent Azikiwe from going to the House of Representatives.

Zik won a regional assembly seat from Lagos, but the opposition party claimed a majority in the House of Assembly and Azikiwe did not represent Lagos in the federal House of Representatives. In 1951, he became leader of the Opposition to the government of Obafemi Awolowo in the Western Region’s House of Assembly. Azikiwe’s non-selection to the national assembly caused chaos in the west.

An agreement by elected NCNC members from Lagos to step down for Azikiwe if he was not nominated broke down. Azikiwe blamed the constitution, and wanted changes made. The NCNC (which dominated the Eastern Region) agreed, and committed to amending the constitution.

Azikiwe moved to the Eastern Region in 1952 and the NCNC-dominated regional assembly made proposals to accommodate him. Although the party’s regional and central ministers were asked to resign in a cabinet reshuffle, most ignored the request. The regional assembly then passed a vote of no confidence on the ministers, and appropriation bills sent to the ministry were rejected. This created an impasse in the region, and the lieutenant governor dissolved the regional house. A new election returned Azikiwe as a member of the Eastern Assembly. He was selected as Chief Minister, and became premier of Nigeria’s Eastern Region in 1954 when it became a federating unit.

Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe became Governor-General on November 16, 1960 (his birthday), with Abubakar Tafawa Balewa as Prime Minister, and became the first Nigerian named to the Privy Council of the United Kingdom. When Nigeria became a republic in 1963, he was its first president. In both posts, Azikiwe’s role was largely ceremonial.

He and his civilian colleagues were removed from office in the January 15, 1966 military coup, and he was the most prominent politician to avoid assassination after the coup.

HONOUR

After the war, Zik was chancellor of the University of Lagos from 1972 to 1976. He joined the Nigerian People’s Party in 1978, making unsuccessful bids for the presidency in 1979 and 1983. He left politics involuntarily after the December 31 1983 military coup.

Azikiwe died at the age 91 on May 11, 1996 at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu following to a protracted illness. He was buried in his native Onitsha.

Places named after Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe include: Azikiwe-Nkrumah Hall, the oldest building on the Lincoln University campus; Nnamdi Azikwe Hall, University of Ibadan; Nnamdi Azikiwe International Airport in Abuja; Nnamdi Azikiwe Stadium in Enugu; Nnamdi Azikiwe University in Awka; Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital in Nnewi; Nnamdi Azikiwe Library at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka; Nnamdi Azikiwe Press Centre, Dodan Barracks, Obalende, Ikoyi, Lagos; Azikiwe Avenue in Dares Salaam, Tanzania, Awka, Enugu and other major towns in Nigeria; is picture appears on Nigeria’s ₦500 banknote since 2001.

Dr, Nnamdi zikiwe was inducted into the Agbalanze society of Onitsha as Nnanyelugo in 1946, recognition for Onitsha men with significant accomplishments. In 1962, he became a second-rank red cap chieftain (Ndichie Okwa) as the Oziziani Obi. Chief Azikiwe was installed as the Owelle-Osowa-Anya of Onitsha in 1972, making him a first-rank hereditary red cap nobleman (Ndichie Ume) in the Igbo branch of the Nigerian chieftaincy system.

He established the University of Nigeria, Nsukka in 1960 and Queen Elizabeth the second appointed him to the Privy Council of the United Kingdom. He was made Grand Commander of the Federal Republic (GCFR), Nigeria’s highest national honour, in 1980.

SPORTS

In his early stages in life, Nnamdi Azikiwe competed in boxing, athletics, swimming, football and tennis. Football was brought to Nigeria by the British as they colonized Africa. However, any leagues that were formed were segregated. Zik of africa saw this as an injustice and he emerged as a leader in terms of connection sports and politics at the end of the colonial period.

In 1934, Zik was denied the right to compete in a track and field event because Nigeria was not allowed to participate. This happened another time because of his Igbo background, and Zik decided that enough was enough and wanted to create his own club. Nnamdi Azikiwe founded Zik’s Athletic Club (ZAC), which opened its doors to sportsmen and women of all races, nationalities, tribes, and classes of Nigeria. Zik was indeed a great man. THANKS